Ann McCarthy1

d. 1840

Ann McCarthy married Henry Lee, son of Maj. Gen. Henry Lee III and Matilda Lee.1 Ann McCarthy died in 1840. She was buried at France.

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia.

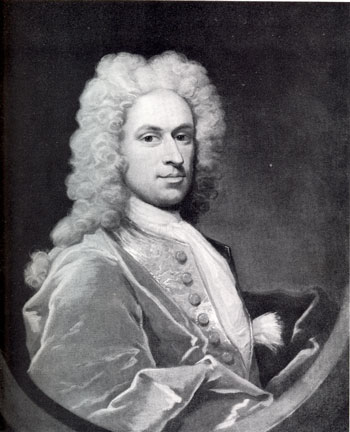

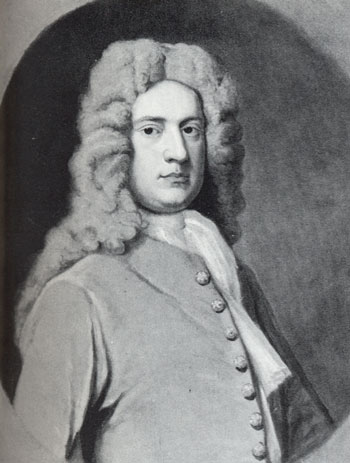

Thomas Lee1

b. 1690, d. 1750

Thomas Lee was born in 1690.1 He was the son of Richard Henry Lee Jr. and Laetita Corbin.1 Thomas Lee married Hannah Ludwell.2 Thomas Lee died in 1750.1

Children of Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell

- Philip Ludwell Lee+2 b. 1727, d. 1775

- Hannah Lee2 b. 1729, d. 1782

- Thomas Ludwell Lee2 b. 1730, d. 1778

- Richard Henry Lee2 b. 20 Jan 1731, d. 19 Jun 1794

- Francis Lightfoot Lee2 b. 14 Oct 1734, d. 11 Jan 1797

- Alice Lee2 b. 1736, d. 1817

- William Lee2 b. 1739, d. 1795

- Arthur Lee2 b. 1740, d. 1792

Elizabeth Collins1

Elizabeth Collins married Richard Bland Lee, son of Maj. Gen Henry Lee II and Lucy Grymes, in 1794.1

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia.

John Lee1

d. February 1630

Child of John Lee and Jane Hancock

- Richard Lee+1 b. 1618, d. 1664

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia, page 8.

Nancy Witcher Langhorne

b. 19 May 1879, d. 2 May 1964

Nancy Witcher Langhorne was also known as Nancy Astor Viscountess Astor. She was born on 19 May 1879 at Danville, VA. She was the daughter of Chiswell Dabney Langhorne and Nancy Witcher Keene. Nancy Witcher Langhorne married William Waldorf Astor. Nancy Witcher Langhorne died on 2 May 1964 at Grimsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England, at age 84. She was buried at Buckinghamshire, England.

Nancy Witcher Astor, Viscountess Astor, CH, (May 19, 1879 – May 2, 1964) was the first woman to serve as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the British House of Commons. (Constance Markiewicz was the first woman elected to serve in the House of Commons after running for the Sinn Féin party in 1918, but in line with Sinn Féin policy she did not take her seat.) She was the wife of Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor.

Astor was born Nancy Witcher Langhorne in Danville, Virginia, in the United States. Her father was Chiswell Dabney Langhorne and her mother was Nancy Witcher Keene. Her father's earlier business venture had depended at least in part upon slave labor and had been badly damaged by the fallout from the American Civil War, causing the family to live in near-poverty for several years before Nancy was born. After her birth her father began working to regain the family wealth, first with a job as an auctioneer and later with a job that he obtained with the railroad by using old contacts from his work as a contractor. By the time she was thirteen years old, the Langhornes were again a rich family with a sizeable home. Chiswell Langhorne later moved the family to their estate, known as Mirador, in Albemarle County, Virginia.

Nancy Langhorne had four sisters and three brothers. All the sisters were known for their beauty; her sister Irene later married the artist Charles Dana Gibson and became a model for the Gibson girl. Nancy and Irene both went to a finishing school in New York City. In New York, Nancy met and married her first husband, Robert Gould Shaw II, a cousin of the Robert Gould Shaw of Fort Wagner fame, on October 27, 1897, when she was 18.

This first marriage was a disaster. Shaw's friends accused Nancy of becoming puritanical and rigid after she married; Nancy's friends contended that Shaw was an alcoholic adulterer. The couple were married for four years and had one son, Bobbie. Nancy left Shaw numerous times during their brief marriage, the first time during their honeymoon. In 1903, Nancy's mother died and Nancy moved back to Mirador to try to run the household, but she was unsuccessful. She left there and took a tour of England, and fell in love with the country while she was there. Because she was so happy there, her father suggested that Nancy move to England. Nancy was reluctant to go, so he suggested that the move had been her mother’s wish and that it would also be good for Nancy's younger sister, Phyllis, to accompany her. Nancy and Phyllis finally moved to England in 1905.

The earlier trip to England had launched Nancy's reputation there as an interesting and witty American. Her tendency to be witty and saucy in conversation, yet religiously devout and almost prudish in behavior, confused many of the English men but pleased some of the older socialites. They liked conversing with the lively and exciting American who at the same time largely conformed to decency and restraint. Nancy also began at this time to show her skill at winning over critics. She was once asked by an English woman, "Have you come to get our husbands?" Her unexpected response, "If you knew the trouble I had getting rid of mine..." charmed her listeners and displayed the wit that would later become famous.

Despite her denial, however, she indeed married an Englishman. Her second husband, Waldorf Astor, was born in the United States but his father had moved the family to England when Waldorf was twelve and raised his children as English aristocrats. The pair was well matched from the start. Not only were they both American expatriates with similar temperaments, but they were of the same age, being born on the exact same day. He shared some of Nancy's moral attitudes, and his heart condition may have encouraged him toward a restraint that she found comforting. The marriage's success, therefore, seemed assured.

After the Astors married, Nancy moved into Cliveden, a lavish estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames, and began her life as a prominent hostess for the social elite. The Astors also owned a grand London house, No. 4 St. James's Square, which is now the premises of the Naval & Military Club. Through her many social connections, Lady Astor became involved in a kind of political circle called Milner's Kindergarten. Considered liberal in their age, the group advocated unity and equality among English-speaking people and a continuance or expansion of British imperialism.

The political significance of Milner's Kindergarten was limited, but it yielded a much more significant result for Lady Astor personally. It was the source of her friendship with Philip Kerr, which was to be one of the most important relationships of her life. Indeed, it came at a critical juncture for both of them. The two met shortly after Kerr had suffered a spiritual crisis regarding his once devout Catholicism. The two of them were both searching for spiritual stability and their search led them toward Christian Science, to which they both eventually converted. Astor's beliefs and activities as a Christian Scientist would become one of the most consistent elements of her life.

Astor's conversion was gradual and was influenced by a number of factors. Her sister Phyllis (who never converted to Christian Science) had given her Science and Health by Mary Baker Eddy because she thought Nancy might find it interesting. At first Lady Astor had only marginal interest, but after a period of illness and surgery she decided that those events had not been what God wanted. In the past, many of her illnesses had been psychosomatic, so the idea of physical illness being a mental construct rang true for her and she embraced the belief system wholeheartedly. At the same time, her former spiritual mentor and good friend, Archdeacon Frederick Neve, disapproved of her conversion and their relationship soured.

Philip Kerr's conversion came only after experimenting with Eastern religion, but he later became a spiritual advisor for Astor. In time, his bitter rejection of Catholicism also influenced Lady Astor, intensifying her opinions in that direction. She was also affected when her friendship with Hillaire Belloc, who was Catholic, began to grow cold because of his disdain for the rich and her efforts to convert his daughters to Christian Science. The loss of that relationship further alienated her against Roman Catholicism. Lady Astor's devotion to Christian Science was more intense than orthodox, and she sent some practitioners away for disagreeing with her. But she was deeply committed to her own interpretation of the faith and held to it almost fanatically. Many of her letters from that time on mentioned Christian Science, and letters from others to her joked about her efforts to convert peers to her beliefs.

During World War I Cliveden was turned into a hospital for Canadian soldiers. Although Astor, as a Christian Scientist, did not believe in the use of medical practices, she got along well with doctors, especially a surgeon named Colonel Mewburn. She justified her position there by helping those who needed non-medical assistance. This work built a public image of Lady Astor as a friend to soldiers, and that proved useful when she ran for office. At the same time, horrible poison gas attacks and the deaths of friends turned her against war itself.

Several elements of Lady Astor's life to this point influenced her first campaign, but the main reason she became a candidate in the first place was her husband's situation. He had enjoyed a promising career for several years before World War I in the House of Commons, but then he succeeded to his father's peerage as the 2nd Viscount Astor. This meant that he automatically became a member of the House of Lords and forfeited his seat of Plymouth Sutton in the House of Commons. So Lady Astor decided to contest the vacant parliamentary seat.

Astor had several disadvantages in her campaign. One of them was her lack of connection with the women's suffrage movement. The first woman elected to the British Parliament, Constance Markiewicz, said Lady Astor was "of the upper classes, out of touch". (While Lady Astor was the first female member of the House of Commons who actually took up her seat, she was not the first woman to be elected to the House. Markiewicz did not take up her seat because of her Irish nationalist views.) Countess Markiewicz had been in Holloway prison for Sinn Féin activities during her election, and other suffragettes had been imprisoned for arson; Astor had no such background. Even more damaging to Astor's campaign were her well-known hostility to alcohol consumption and her ignorance of current political issues. These points did not endear her to the people of Plymouth, the constituency from which she was elected. Perhaps worst of all, her tendency to say odd or outlandish things sometimes made her look rather unstable.

However, Astor also had some positive attributes in her campaign, such as her earlier work with the Canadian soldiers, her other charitable work during the war, her vast financial resources for the campaign and, most of all, her ability to improvise. Her ability to turn the tables on the hecklers was particularly useful. Once a man asked her what the Astors had done for him and she responded with, "Why, Charlie, you know," and later had a picture taken with him. This informal style baffled yet amused the British public. She rallied the supporters of the current government, was pragmatic enough to moderate her Prohibitionist views, and used women’s meetings to gain the support of female voters. A by-election was held on 28 November, 1919, and she took up her seat in the House on 1 December as a Unionist (also known as "Tory") Member of Parliament.

Astor's parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life, making her an object of both love and hatred. Her presence almost immediately gained attention, both as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realizing that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She did try in some ways to minimize disruption by dressing more sedately than usual and by avoiding the bars and smoking rooms frequented by the men.

Early in her first term, a fellow Member of Parliament named Horatio Bottomley, who felt Astor was an obstacle in his desire to dominate the "soldier’s friend" issue, sought to ruin her political career. He did this by capitalizing on the first substantial controversies in which she participated, namely her opposition to divorce reform and her efforts to maintain wartime alcohol restrictions. He depicted her as a hypocrite in his newspaper, saying that the divorce reform bill she opposed allowed women to have the kind of divorce she had had in America. However, a budget crisis and his bitter tone caused this effort to backfire. Bottomley eventually went to prison for fraud, a fact that Astor used to her advantage in later campaigns.

Among Astor's early political friends were the first female candidates to follow her to Parliament, including members of the other parties. The first of these friendships began when Ellen Wintringham was elected after Astor had been in office for two years, but the most surprising might have been her friendship with "Red Ellen" Wilkinson, a former Communist representative in the Labour Party. Astor later proposed creating a "Women’s Party", but the female Labour MPs thought it was a ridiculous idea because at that time their party had power and promised them positions. Astor conceded this, but her closeness with other female MPs dissipated with time and by 1931 she became hostile to female Labour members like Susan Lawrence.

Unlike most female MPs, Lady Astor's accomplishments in the House of Commons were relatively minor. She never held a position with much influence. Indeed, the Duchess of Atholl (elected to Parliament in 1923, four years after Lady Astor) rose to higher levels in the Tory Party before Astor did, and this was largely as Astor wished. She felt that if she had a position in the party, she would be less free to criticize her party’s government. One of her few significant achievements in the House was the passage of a bill she sponsored to increase the legal drinking age to eighteen unless the minor has parental approval.

During this period Lady Astor did some significant work outside the political sphere. The most famous was her support for nursery schools. Her involvement with this cause was somewhat surprising she was introduced to it by a socialist named Margaret McMillan who believed that her dead sister still had a role in guiding her. Lady Astor was initially skeptical, but later the two women became close and Astor used her wealth to aid their social efforts.

Although she was active in charitable efforts, Astor also became noted for a streak of cruelty and callousness. On hearing of the death of a political enemy, she openly expressed her pleasure. When people complained about this, she did not apologize but instead said, "I’m a Virginian; we shoot to kill". A friend from Virginia, Angus McDonnell, had angered her when he married without consulting her after having agreed to seek her permission first. She later told him, regarding his maiden speech, that he "really must do better than that". During the course of her adult life, Astor alienated many others with her sharp words as well.

The 1920s were the most positive period in Parliament for Astor as she made several effective speeches and introduced a bill that passed. Her wealth and persona also brought attention to women who were serving in government. Furthermore, she worked to bring more women into the civil service, the police force, education reform, and the House of Lords. She remained popular in her district and well-liked in the United States during the 1920s, but this period of success is generally believed to have declined in the following decades.

The 1930s were a decade of personal and professional difficulty for Lady Astor. An early sign of future problems came in 1928 when she won only a narrow victory over the Labour candidate. In 1931 her problems became more acute when Bobbie, her son from her first marriage, was arrested for homosexuality. Because Bobbie had previously shown tendencies toward alcoholism and instability, Astor's friend Philip Kerr, now Marquess of Lothian, told her that the arrest might be positive for him. This prediction would turn out to be incorrect. Astor also made a disastrous speech stating that alcohol use was the reason England's national cricket team was defeated by the Australian national cricket team. Both the English and Australian teams objected to this statement. Astor remained oblivious to her growing unpopularity almost to the end.

A mixed element in these difficult years was Astor's friendship with George Bernard Shaw. He helped her through some of her problems, but also made some things worse. They held opposing political views and had very different temperaments, but he liked her as a fellow non-conformist, and she had a fondness for writers in general. Nevertheless, his tendency to make controversial statements or put her into awkward situations proved to be a drawback for her.

After Astor's son Bobbie was arrested, Shaw invited her to accompany him on his trip to the Soviet Union. Although it was helpful in some ways, this trip turned out to be bad overall for Lady Astor's political career. During the trip Shaw made many flattering statements about Stalinist Russia, while Nancy often disparaged it because she did not approve of Communism. She even asked Stalin directly why he had slaughtered so many Russians, but many of her criticisms were translated into innocuous statements instead, leading many of her conservative supporters to fear she had "gone soft" on Communism. (Her question to Stalin may have been translated correctly only because he insisted that he be told what she had actually said.) Furthermore, Shaw's praise of the USSR made the trip seem like a coup for Soviet propaganda and made her presence there disturbing for the Tories.

The tarnishing of Lady Astor's image accelerated due to the rise of Nazism. Although Astor had criticized the Nazis for devaluing the position of women, she was also adamantly opposed to the idea of another World War. Several of her friends and associates, especially Lord Lothian (Philip Kerr), became heavily involved in the German appeasement policy; this group became known as the "Cliveden set". The term was first used in The Week, a newspaper that was run by reformist Claud Cockburn, but over time the allegations became more elaborate. The Cliveden set was seen variously as the prime mover for appeasement, or a society that secretly ran the nation, or even as a beachhead for Nazism in Britain. Astor was viewed by some as Hitler's woman in Britain, and some went so far as to claim that she had hypnotic powers.

Lady Astor also had a close friendship with Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and the correspondence between them is reportedly filled with anti-Semitic language. As Edward Renehan notes:

As fiercely anti-Communist as they were anti-Semitic, Kennedy and Astor looked upon Adolf Hitler as a welcome solution to both of these "world problems" (Nancy's phrase).... Kennedy replied that he expected the "Jew media" in the United States to become a problem, that "Jewish pundits in New York and Los Angeles" were already making noises contrived to "set a match to the fuse of the world."

Lady Astor's actual connection to anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi policies is, however, debatable. Astor did occasionally meet with Nazi officials in keeping with Neville Chamberlain's policies, and it is true that she distrusted and disliked British Foreign Secretary (later Prime Minister) Anthony Eden, stating that the more she saw of him the "more certain" she was that he would "never be a Disraeli". She told one Nazi official, who later turned out to be working against Nazis from within, that she supported their re-armament, but she supported this policy because Germany was "surrounded by Catholics" in her opinion. She also told Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador who would later become the Foreign Minister of Germany, that Hitler looked too much like Charlie Chaplin to be taken seriously. These statements are the only documented incidents of Nazi sympathy directed to actual Nazis.

Lady Astor did not seem to be bothered by the fact that so many of her public statements caused difficulties. She became increasingly harsher in her anti-Catholic and anti-Communist sentiments. After passage of the Munich Agreement, she said that if the Czech refugees fleeing Nazi oppression were Communists, they should seek asylum with the Soviets instead of the British. Even supporters of appeasement felt that this was out of line, but Lord Lothian encouraged her attitudes. He railed against the pope for not supporting Hitler's annexation of Austria and his words influenced Lady Astor in many ways.

When war did come, Astor admitted that she had made mistakes, and even voted against Chamberlain, but hostility remained. She was taken far less seriously than before, with some calling her "The Honourable Member for Berlin." In addition, her abilities as an MP had declined with age. Her increasing fear of Catholics led her to make a speech regarding her belief that a Catholic conspiracy was subverting the foreign office. Her long-time hatred of Communists continued and she insulted Stalin's role as an ally during the war. Her speeches became rambling and incomprehensible, and even her enemies lamented that debating her had become "like playing squash with a dish of scrambled eggs". She had become more of a joke than an adversary to her enemies.

The period from 1937 to the end of the war was traumatic on a personal level. In the period of 1937-38 Astor's sister Phyllis and only surviving brother died. In 1940 her close friend and spiritual advisor Lord Lothian died as well. Although his influence had a definite negative aspect, he had been her closest Christian Scientist friend even after her husband converted. George Bernard Shaw’s wife also died about two years later. During the war, Astor got into a fight with her husband about chocolate and soon after he had a heart attack. After this, their marriage grew cold, probably due at least in part to the harsh effects of such a petty argument and her subsequent discomfort with his health problems. She ran a hospital for Canadian soldiers as she had before, but openly expressed a preference for the veterans of the previous World War.

It is generally believed that it was Lady Astor who, during a World War II speech, first referred to the men of the 8th Army who were fighting in the Italian campaign as the "D-Day Dodgers". Her implication was that they had it easy because they were avoiding the "real war" in France and the future invasion. The Allied soldiers in Italy were so incensed that Major Hamish Henderson of the 51st Highland Division composed a bitingly sarcastic song to the tune of the haunting German song Lili Marleen (popularised in English by Marlene Dietrich) called "The Ballad Of The D-Day Dodgers". One stanza says, "Dear Lady Astor, we think you know a lot/Standing on your platform and talking tommy rot./You're England's sweetheart and its pride;/We think you're mouth's too bleeding wide./That's from your 'D-Day Dodgers' in sunny Italy."

Lady Astor also made a disparaging remark about troops involved in the Burma Campaign, warning the public to "beware the men with crows' feet". This was an allusion to the white lines often found around the eyes of white soldiers in hot climates due to squinting in the bright sunlight as it tanned their faces. Soldiers of the UK's 14th Army were slightly bemused to be accorded such attention and it was strongly rumored among them that her prejudice was the result of a 14th Army officer on leave either impregnating Astor's daughter or infecting her with a sexually transmitted disease.

Lady Astor did not feel that her final years were a period of personal decline. Instead, in her opinion, it was her party and her husband who caused her retirement in 1945. The Tories felt that she had become a liability in the final years of World War II, and her husband told her that if she ran for office again the family would not support her. She conceded, but with irritation and anger, according to contemporary reports.

Lady Astor's retirement years proved difficult, especially for her marriage. She publicly blamed her husband for forcing her to retire; for example, in a speech commemorating her 25 years in office she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began traveling separately and living apart soon after. Lord Astor also began moving toward left-wing politics in his last years, and that exacerbated their differences. However, the couple reconciled before his death on 30 September 1952.

This period also proved to be hard on Lady Astor's public image. Her racial views were increasingly out of touch with cultural changes, and she expressed a growing paranoia regarding ethnic minorities. In one instance she stated that the President of the United States had become too dependent on New York City. To her this city represented "Jewish and foreign" influences that she feared. During her U.S. tour she told a group of African American students that they should aspire to be like the Black servants she remembered from her youth. On a later trip she told African American church members that they should be grateful for slavery because it had allowed them to be introduced to Christianity. In Rhodesia she proudly told the White minority government leaders that she was the daughter of a slave owner.

After 1956 Lady Astor became increasingly isolated. Her sisters had all died, "Red Ellen" Wilkinson died in 1947, George Bernard Shaw died in 1950, and she did not take well to widowhood. Her son Bobbie became increasingly combative and after her death he committed suicide. Her son Jakie married a prominent Catholic woman, which hurt his relationship with his mother, and her other children became estranged from her. Ironically, these events mellowed her and she began to accept Catholics as friends. However, she stated that her final years were lonely. Lady Astor died in 1964 at her daughter's home at Grimsthorpe in Lincolnshire. She was buried in Buckinghamshire, England.

Nancy Witcher Astor, Viscountess Astor, CH, (May 19, 1879 – May 2, 1964) was the first woman to serve as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the British House of Commons. (Constance Markiewicz was the first woman elected to serve in the House of Commons after running for the Sinn Féin party in 1918, but in line with Sinn Féin policy she did not take her seat.) She was the wife of Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor.

Astor was born Nancy Witcher Langhorne in Danville, Virginia, in the United States. Her father was Chiswell Dabney Langhorne and her mother was Nancy Witcher Keene. Her father's earlier business venture had depended at least in part upon slave labor and had been badly damaged by the fallout from the American Civil War, causing the family to live in near-poverty for several years before Nancy was born. After her birth her father began working to regain the family wealth, first with a job as an auctioneer and later with a job that he obtained with the railroad by using old contacts from his work as a contractor. By the time she was thirteen years old, the Langhornes were again a rich family with a sizeable home. Chiswell Langhorne later moved the family to their estate, known as Mirador, in Albemarle County, Virginia.

Nancy Langhorne had four sisters and three brothers. All the sisters were known for their beauty; her sister Irene later married the artist Charles Dana Gibson and became a model for the Gibson girl. Nancy and Irene both went to a finishing school in New York City. In New York, Nancy met and married her first husband, Robert Gould Shaw II, a cousin of the Robert Gould Shaw of Fort Wagner fame, on October 27, 1897, when she was 18.

This first marriage was a disaster. Shaw's friends accused Nancy of becoming puritanical and rigid after she married; Nancy's friends contended that Shaw was an alcoholic adulterer. The couple were married for four years and had one son, Bobbie. Nancy left Shaw numerous times during their brief marriage, the first time during their honeymoon. In 1903, Nancy's mother died and Nancy moved back to Mirador to try to run the household, but she was unsuccessful. She left there and took a tour of England, and fell in love with the country while she was there. Because she was so happy there, her father suggested that Nancy move to England. Nancy was reluctant to go, so he suggested that the move had been her mother’s wish and that it would also be good for Nancy's younger sister, Phyllis, to accompany her. Nancy and Phyllis finally moved to England in 1905.

The earlier trip to England had launched Nancy's reputation there as an interesting and witty American. Her tendency to be witty and saucy in conversation, yet religiously devout and almost prudish in behavior, confused many of the English men but pleased some of the older socialites. They liked conversing with the lively and exciting American who at the same time largely conformed to decency and restraint. Nancy also began at this time to show her skill at winning over critics. She was once asked by an English woman, "Have you come to get our husbands?" Her unexpected response, "If you knew the trouble I had getting rid of mine..." charmed her listeners and displayed the wit that would later become famous.

Despite her denial, however, she indeed married an Englishman. Her second husband, Waldorf Astor, was born in the United States but his father had moved the family to England when Waldorf was twelve and raised his children as English aristocrats. The pair was well matched from the start. Not only were they both American expatriates with similar temperaments, but they were of the same age, being born on the exact same day. He shared some of Nancy's moral attitudes, and his heart condition may have encouraged him toward a restraint that she found comforting. The marriage's success, therefore, seemed assured.

After the Astors married, Nancy moved into Cliveden, a lavish estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames, and began her life as a prominent hostess for the social elite. The Astors also owned a grand London house, No. 4 St. James's Square, which is now the premises of the Naval & Military Club. Through her many social connections, Lady Astor became involved in a kind of political circle called Milner's Kindergarten. Considered liberal in their age, the group advocated unity and equality among English-speaking people and a continuance or expansion of British imperialism.

The political significance of Milner's Kindergarten was limited, but it yielded a much more significant result for Lady Astor personally. It was the source of her friendship with Philip Kerr, which was to be one of the most important relationships of her life. Indeed, it came at a critical juncture for both of them. The two met shortly after Kerr had suffered a spiritual crisis regarding his once devout Catholicism. The two of them were both searching for spiritual stability and their search led them toward Christian Science, to which they both eventually converted. Astor's beliefs and activities as a Christian Scientist would become one of the most consistent elements of her life.

Astor's conversion was gradual and was influenced by a number of factors. Her sister Phyllis (who never converted to Christian Science) had given her Science and Health by Mary Baker Eddy because she thought Nancy might find it interesting. At first Lady Astor had only marginal interest, but after a period of illness and surgery she decided that those events had not been what God wanted. In the past, many of her illnesses had been psychosomatic, so the idea of physical illness being a mental construct rang true for her and she embraced the belief system wholeheartedly. At the same time, her former spiritual mentor and good friend, Archdeacon Frederick Neve, disapproved of her conversion and their relationship soured.

Philip Kerr's conversion came only after experimenting with Eastern religion, but he later became a spiritual advisor for Astor. In time, his bitter rejection of Catholicism also influenced Lady Astor, intensifying her opinions in that direction. She was also affected when her friendship with Hillaire Belloc, who was Catholic, began to grow cold because of his disdain for the rich and her efforts to convert his daughters to Christian Science. The loss of that relationship further alienated her against Roman Catholicism. Lady Astor's devotion to Christian Science was more intense than orthodox, and she sent some practitioners away for disagreeing with her. But she was deeply committed to her own interpretation of the faith and held to it almost fanatically. Many of her letters from that time on mentioned Christian Science, and letters from others to her joked about her efforts to convert peers to her beliefs.

During World War I Cliveden was turned into a hospital for Canadian soldiers. Although Astor, as a Christian Scientist, did not believe in the use of medical practices, she got along well with doctors, especially a surgeon named Colonel Mewburn. She justified her position there by helping those who needed non-medical assistance. This work built a public image of Lady Astor as a friend to soldiers, and that proved useful when she ran for office. At the same time, horrible poison gas attacks and the deaths of friends turned her against war itself.

Several elements of Lady Astor's life to this point influenced her first campaign, but the main reason she became a candidate in the first place was her husband's situation. He had enjoyed a promising career for several years before World War I in the House of Commons, but then he succeeded to his father's peerage as the 2nd Viscount Astor. This meant that he automatically became a member of the House of Lords and forfeited his seat of Plymouth Sutton in the House of Commons. So Lady Astor decided to contest the vacant parliamentary seat.

Astor had several disadvantages in her campaign. One of them was her lack of connection with the women's suffrage movement. The first woman elected to the British Parliament, Constance Markiewicz, said Lady Astor was "of the upper classes, out of touch". (While Lady Astor was the first female member of the House of Commons who actually took up her seat, she was not the first woman to be elected to the House. Markiewicz did not take up her seat because of her Irish nationalist views.) Countess Markiewicz had been in Holloway prison for Sinn Féin activities during her election, and other suffragettes had been imprisoned for arson; Astor had no such background. Even more damaging to Astor's campaign were her well-known hostility to alcohol consumption and her ignorance of current political issues. These points did not endear her to the people of Plymouth, the constituency from which she was elected. Perhaps worst of all, her tendency to say odd or outlandish things sometimes made her look rather unstable.

However, Astor also had some positive attributes in her campaign, such as her earlier work with the Canadian soldiers, her other charitable work during the war, her vast financial resources for the campaign and, most of all, her ability to improvise. Her ability to turn the tables on the hecklers was particularly useful. Once a man asked her what the Astors had done for him and she responded with, "Why, Charlie, you know," and later had a picture taken with him. This informal style baffled yet amused the British public. She rallied the supporters of the current government, was pragmatic enough to moderate her Prohibitionist views, and used women’s meetings to gain the support of female voters. A by-election was held on 28 November, 1919, and she took up her seat in the House on 1 December as a Unionist (also known as "Tory") Member of Parliament.

Astor's parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life, making her an object of both love and hatred. Her presence almost immediately gained attention, both as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realizing that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She did try in some ways to minimize disruption by dressing more sedately than usual and by avoiding the bars and smoking rooms frequented by the men.

Early in her first term, a fellow Member of Parliament named Horatio Bottomley, who felt Astor was an obstacle in his desire to dominate the "soldier’s friend" issue, sought to ruin her political career. He did this by capitalizing on the first substantial controversies in which she participated, namely her opposition to divorce reform and her efforts to maintain wartime alcohol restrictions. He depicted her as a hypocrite in his newspaper, saying that the divorce reform bill she opposed allowed women to have the kind of divorce she had had in America. However, a budget crisis and his bitter tone caused this effort to backfire. Bottomley eventually went to prison for fraud, a fact that Astor used to her advantage in later campaigns.

Among Astor's early political friends were the first female candidates to follow her to Parliament, including members of the other parties. The first of these friendships began when Ellen Wintringham was elected after Astor had been in office for two years, but the most surprising might have been her friendship with "Red Ellen" Wilkinson, a former Communist representative in the Labour Party. Astor later proposed creating a "Women’s Party", but the female Labour MPs thought it was a ridiculous idea because at that time their party had power and promised them positions. Astor conceded this, but her closeness with other female MPs dissipated with time and by 1931 she became hostile to female Labour members like Susan Lawrence.

Unlike most female MPs, Lady Astor's accomplishments in the House of Commons were relatively minor. She never held a position with much influence. Indeed, the Duchess of Atholl (elected to Parliament in 1923, four years after Lady Astor) rose to higher levels in the Tory Party before Astor did, and this was largely as Astor wished. She felt that if she had a position in the party, she would be less free to criticize her party’s government. One of her few significant achievements in the House was the passage of a bill she sponsored to increase the legal drinking age to eighteen unless the minor has parental approval.

During this period Lady Astor did some significant work outside the political sphere. The most famous was her support for nursery schools. Her involvement with this cause was somewhat surprising she was introduced to it by a socialist named Margaret McMillan who believed that her dead sister still had a role in guiding her. Lady Astor was initially skeptical, but later the two women became close and Astor used her wealth to aid their social efforts.

Although she was active in charitable efforts, Astor also became noted for a streak of cruelty and callousness. On hearing of the death of a political enemy, she openly expressed her pleasure. When people complained about this, she did not apologize but instead said, "I’m a Virginian; we shoot to kill". A friend from Virginia, Angus McDonnell, had angered her when he married without consulting her after having agreed to seek her permission first. She later told him, regarding his maiden speech, that he "really must do better than that". During the course of her adult life, Astor alienated many others with her sharp words as well.

The 1920s were the most positive period in Parliament for Astor as she made several effective speeches and introduced a bill that passed. Her wealth and persona also brought attention to women who were serving in government. Furthermore, she worked to bring more women into the civil service, the police force, education reform, and the House of Lords. She remained popular in her district and well-liked in the United States during the 1920s, but this period of success is generally believed to have declined in the following decades.

The 1930s were a decade of personal and professional difficulty for Lady Astor. An early sign of future problems came in 1928 when she won only a narrow victory over the Labour candidate. In 1931 her problems became more acute when Bobbie, her son from her first marriage, was arrested for homosexuality. Because Bobbie had previously shown tendencies toward alcoholism and instability, Astor's friend Philip Kerr, now Marquess of Lothian, told her that the arrest might be positive for him. This prediction would turn out to be incorrect. Astor also made a disastrous speech stating that alcohol use was the reason England's national cricket team was defeated by the Australian national cricket team. Both the English and Australian teams objected to this statement. Astor remained oblivious to her growing unpopularity almost to the end.

A mixed element in these difficult years was Astor's friendship with George Bernard Shaw. He helped her through some of her problems, but also made some things worse. They held opposing political views and had very different temperaments, but he liked her as a fellow non-conformist, and she had a fondness for writers in general. Nevertheless, his tendency to make controversial statements or put her into awkward situations proved to be a drawback for her.

After Astor's son Bobbie was arrested, Shaw invited her to accompany him on his trip to the Soviet Union. Although it was helpful in some ways, this trip turned out to be bad overall for Lady Astor's political career. During the trip Shaw made many flattering statements about Stalinist Russia, while Nancy often disparaged it because she did not approve of Communism. She even asked Stalin directly why he had slaughtered so many Russians, but many of her criticisms were translated into innocuous statements instead, leading many of her conservative supporters to fear she had "gone soft" on Communism. (Her question to Stalin may have been translated correctly only because he insisted that he be told what she had actually said.) Furthermore, Shaw's praise of the USSR made the trip seem like a coup for Soviet propaganda and made her presence there disturbing for the Tories.

The tarnishing of Lady Astor's image accelerated due to the rise of Nazism. Although Astor had criticized the Nazis for devaluing the position of women, she was also adamantly opposed to the idea of another World War. Several of her friends and associates, especially Lord Lothian (Philip Kerr), became heavily involved in the German appeasement policy; this group became known as the "Cliveden set". The term was first used in The Week, a newspaper that was run by reformist Claud Cockburn, but over time the allegations became more elaborate. The Cliveden set was seen variously as the prime mover for appeasement, or a society that secretly ran the nation, or even as a beachhead for Nazism in Britain. Astor was viewed by some as Hitler's woman in Britain, and some went so far as to claim that she had hypnotic powers.

Lady Astor also had a close friendship with Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., and the correspondence between them is reportedly filled with anti-Semitic language. As Edward Renehan notes:

As fiercely anti-Communist as they were anti-Semitic, Kennedy and Astor looked upon Adolf Hitler as a welcome solution to both of these "world problems" (Nancy's phrase).... Kennedy replied that he expected the "Jew media" in the United States to become a problem, that "Jewish pundits in New York and Los Angeles" were already making noises contrived to "set a match to the fuse of the world."

Lady Astor's actual connection to anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi policies is, however, debatable. Astor did occasionally meet with Nazi officials in keeping with Neville Chamberlain's policies, and it is true that she distrusted and disliked British Foreign Secretary (later Prime Minister) Anthony Eden, stating that the more she saw of him the "more certain" she was that he would "never be a Disraeli". She told one Nazi official, who later turned out to be working against Nazis from within, that she supported their re-armament, but she supported this policy because Germany was "surrounded by Catholics" in her opinion. She also told Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador who would later become the Foreign Minister of Germany, that Hitler looked too much like Charlie Chaplin to be taken seriously. These statements are the only documented incidents of Nazi sympathy directed to actual Nazis.

Lady Astor did not seem to be bothered by the fact that so many of her public statements caused difficulties. She became increasingly harsher in her anti-Catholic and anti-Communist sentiments. After passage of the Munich Agreement, she said that if the Czech refugees fleeing Nazi oppression were Communists, they should seek asylum with the Soviets instead of the British. Even supporters of appeasement felt that this was out of line, but Lord Lothian encouraged her attitudes. He railed against the pope for not supporting Hitler's annexation of Austria and his words influenced Lady Astor in many ways.

When war did come, Astor admitted that she had made mistakes, and even voted against Chamberlain, but hostility remained. She was taken far less seriously than before, with some calling her "The Honourable Member for Berlin." In addition, her abilities as an MP had declined with age. Her increasing fear of Catholics led her to make a speech regarding her belief that a Catholic conspiracy was subverting the foreign office. Her long-time hatred of Communists continued and she insulted Stalin's role as an ally during the war. Her speeches became rambling and incomprehensible, and even her enemies lamented that debating her had become "like playing squash with a dish of scrambled eggs". She had become more of a joke than an adversary to her enemies.

The period from 1937 to the end of the war was traumatic on a personal level. In the period of 1937-38 Astor's sister Phyllis and only surviving brother died. In 1940 her close friend and spiritual advisor Lord Lothian died as well. Although his influence had a definite negative aspect, he had been her closest Christian Scientist friend even after her husband converted. George Bernard Shaw’s wife also died about two years later. During the war, Astor got into a fight with her husband about chocolate and soon after he had a heart attack. After this, their marriage grew cold, probably due at least in part to the harsh effects of such a petty argument and her subsequent discomfort with his health problems. She ran a hospital for Canadian soldiers as she had before, but openly expressed a preference for the veterans of the previous World War.

It is generally believed that it was Lady Astor who, during a World War II speech, first referred to the men of the 8th Army who were fighting in the Italian campaign as the "D-Day Dodgers". Her implication was that they had it easy because they were avoiding the "real war" in France and the future invasion. The Allied soldiers in Italy were so incensed that Major Hamish Henderson of the 51st Highland Division composed a bitingly sarcastic song to the tune of the haunting German song Lili Marleen (popularised in English by Marlene Dietrich) called "The Ballad Of The D-Day Dodgers". One stanza says, "Dear Lady Astor, we think you know a lot/Standing on your platform and talking tommy rot./You're England's sweetheart and its pride;/We think you're mouth's too bleeding wide./That's from your 'D-Day Dodgers' in sunny Italy."

Lady Astor also made a disparaging remark about troops involved in the Burma Campaign, warning the public to "beware the men with crows' feet". This was an allusion to the white lines often found around the eyes of white soldiers in hot climates due to squinting in the bright sunlight as it tanned their faces. Soldiers of the UK's 14th Army were slightly bemused to be accorded such attention and it was strongly rumored among them that her prejudice was the result of a 14th Army officer on leave either impregnating Astor's daughter or infecting her with a sexually transmitted disease.

Lady Astor did not feel that her final years were a period of personal decline. Instead, in her opinion, it was her party and her husband who caused her retirement in 1945. The Tories felt that she had become a liability in the final years of World War II, and her husband told her that if she ran for office again the family would not support her. She conceded, but with irritation and anger, according to contemporary reports.

Lady Astor's retirement years proved difficult, especially for her marriage. She publicly blamed her husband for forcing her to retire; for example, in a speech commemorating her 25 years in office she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began traveling separately and living apart soon after. Lord Astor also began moving toward left-wing politics in his last years, and that exacerbated their differences. However, the couple reconciled before his death on 30 September 1952.

This period also proved to be hard on Lady Astor's public image. Her racial views were increasingly out of touch with cultural changes, and she expressed a growing paranoia regarding ethnic minorities. In one instance she stated that the President of the United States had become too dependent on New York City. To her this city represented "Jewish and foreign" influences that she feared. During her U.S. tour she told a group of African American students that they should aspire to be like the Black servants she remembered from her youth. On a later trip she told African American church members that they should be grateful for slavery because it had allowed them to be introduced to Christianity. In Rhodesia she proudly told the White minority government leaders that she was the daughter of a slave owner.

After 1956 Lady Astor became increasingly isolated. Her sisters had all died, "Red Ellen" Wilkinson died in 1947, George Bernard Shaw died in 1950, and she did not take well to widowhood. Her son Bobbie became increasingly combative and after her death he committed suicide. Her son Jakie married a prominent Catholic woman, which hurt his relationship with his mother, and her other children became estranged from her. Ironically, these events mellowed her and she began to accept Catholics as friends. However, she stated that her final years were lonely. Lady Astor died in 1964 at her daughter's home at Grimsthorpe in Lincolnshire. She was buried in Buckinghamshire, England.

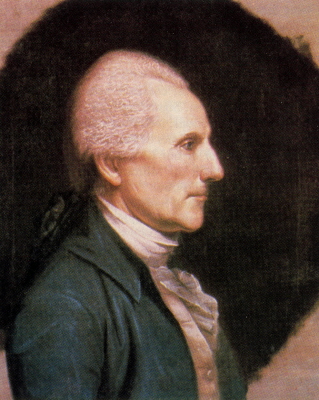

Richard Henry Lee1

b. 20 January 1731, d. 19 June 1794

Richard Henry Lee was born on 20 January 1731 at Stratford, Westmoreland Co., VA.1,2 He was the son of Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell.1 Richard Henry Lee married Anne Aylett on 3 December 1757.2 Richard Henry Lee married Anne Gaskins in June 1769.2 Richard Henry Lee died on 19 June 1794 at Chantilly, Westmoreland Co., VA, at age 63.1,2

Richard signed the Declaration of Independence as a member of the Virginia Delegation. In addition to the ususal home tutorial education, he had the advantage of extensive study at the Wakefield Academy in Yorkshire, England. Beginning in 1757, Richard entered upon a public career serving in the House of Burgesses and later as a Justice of the Peace. At the end of the French and Indian War, as Parliament sought ways to tax teh colonies to pay for the large expenses incurred, Lee found himself in opposition to these approaches and ws soon in the forefront of defending colonial rights. He reisited both the Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts, and suggested a means of intercolonial correspondence that was brought to fruition in 1773. He was named as a Delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774.

He was elected tot he Second Continental Congress where his most outstanding act was the introduction on 7 June 1776 of the Resolution, "That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britian is, and outht to be, totally dissolved." He was a State Legislator from 1780-84, returned to the Congress until 1789, and led opposition to the Federal Constitution, but was elected to the new U.S. Senate in 1789, from which he resigned in 1792. 3

Sources differ on his birth date with some showing 1731, others 1733.

Richard signed the Declaration of Independence as a member of the Virginia Delegation. In addition to the ususal home tutorial education, he had the advantage of extensive study at the Wakefield Academy in Yorkshire, England. Beginning in 1757, Richard entered upon a public career serving in the House of Burgesses and later as a Justice of the Peace. At the end of the French and Indian War, as Parliament sought ways to tax teh colonies to pay for the large expenses incurred, Lee found himself in opposition to these approaches and ws soon in the forefront of defending colonial rights. He reisited both the Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts, and suggested a means of intercolonial correspondence that was brought to fruition in 1773. He was named as a Delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774.

He was elected tot he Second Continental Congress where his most outstanding act was the introduction on 7 June 1776 of the Resolution, "That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britian is, and outht to be, totally dissolved." He was a State Legislator from 1780-84, returned to the Congress until 1789, and led opposition to the Federal Constitution, but was elected to the new U.S. Senate in 1789, from which he resigned in 1792. 3

Sources differ on his birth date with some showing 1731, others 1733.

Robert Edward Lee Jr.

b. 27 October 1843, d. 19 October 1914

Robert Edward Lee Jr. was born on 27 October 1843 at Arlington, Alexandria Co., VA.1,2 He was the son of Gen. Robert Edward Lee and Mary Anne Randolph Custis.2 Robert Edward Lee Jr. married Juliet Gaines Carter, daughter of Thomas Henry Carter and Susan Elizabeth Roy, on 8 March 1894.1,2 Robert Edward Lee Jr. died on 19 October 1914 at Nordley, Fauquier Co., VA, at age 70.1,2

Sarah Elizabeth Dabney

b. 14 April 1821, d. 26 February 1884

Sarah Elizabeth Dabney was born on 14 April 1821 at Lynchburg, Campbell Co., VA. She was the daughter of Chiswell Dabney and Nancy Wythe.1 Sarah Elizabeth Dabney married John S. Langhorne on 14 February 1839 at Lynchburg, Campbell Co., VA. Sarah Elizabeth Dabney died on 26 February 1884 at Lynchburg, Campbell Co., VA, at age 62.

Child of Sarah Elizabeth Dabney and John S. Langhorne

- Chiswell Dabney Langhorne+ b. 4 Nov 1843, d. 14 Feb 1919

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Daniel Parke Custis

b. 15 October 1711, d. 8 July 1757

Daniel Parke Custis was born on 15 October 1711. He married Martha Dandridge, daughter of John Dandridge and Frances Jones, on 15 May 1750. Daniel Parke Custis died on 8 July 1757 at age 45.

Child of Daniel Parke Custis and Martha Dandridge

- John Parke Custis+ b. 27 Nov 1754, d. 5 Nov 1781

Nancy Wythe1

Nancy Wythe married Chiswell Dabney, son of Capt. George Dabney and Elizabeth Price, in 1816 at VA.1

Child of Nancy Wythe and Chiswell Dabney

- Sarah Elizabeth Dabney+1 b. 14 Apr 1821, d. 26 Feb 1884

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Thomas Ludwell Lee1

b. 1730, d. 1778

Thomas Ludwell Lee was born in 1730.1 He was the son of Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell.1 Thomas Ludwell Lee died in 1778.1

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia.

Elizabeth Price1

b. circa 1740, d. 1819

Elizabeth Price was born circa 1740 at VA.1 She was the daughter of John Price and Mary Randolph. Elizabeth Price married Capt. George Dabney circa 1762 at VA.1 Elizabeth Price died in 1819 at VA.1

Child of Elizabeth Price and Capt. George Dabney

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Richard Bland

b. 11 August 1665, d. 6 April 1720

Richard Bland was born on 11 August 1665 at Berkeley, Charles City Co., VA. He married Elizabeth Randolph, daughter of William Randolph and Mary Isham, on 11 February 1701/2. Richard Bland died on 6 April 1720 at age 54.

Child of Richard Bland and Elizabeth Randolph

- Richard Bland1 b. 6 May 1710, d. 26 Oct 1776

Citations

- [S690] ANB, online http://www.anb.org

Dorothy Bradstreet

b. 1633

Dorothy Bradstreet was born in 1633 at Salem, Essex Co., MA. She was the daughter of Gov. Simon Bradstreet and Anne Dudley.

Beverley Randolph1

b. 1744, d. February 1797

Beverley Randolph was born in 1744.1 He was the son of Peter Randolph and Lucy Bolling.1 Beverley Randolph died in February 1797 at on his farm near Green Creek, Cumberland Co., VA.1 He was buried at Westview Cemetery, Farmville, VA.

Beverley served in the militia during the Revolutionary War, was a member of the Viorginia Assembly and was a member of the state's House of Delegates from 1777 to 1780. He was elected Governor in 1788, he first to be elected after Virginia ratified the U.S. Constitution.

Beverley served in the militia during the Revolutionary War, was a member of the Viorginia Assembly and was a member of the state's House of Delegates from 1777 to 1780. He was elected Governor in 1788, he first to be elected after Virginia ratified the U.S. Constitution.

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Mercy Bradstreet

b. 1647

Mercy Bradstreet was born in 1647 at Andover, Essex Co., MA. She was the daughter of Gov. Simon Bradstreet and Anne Dudley.

Frank Hathaway

b. 1876

Hannah Bradstreet

b. 1654

Hannah Bradstreet was born in 1654 at Ipswich, Essex Co., MA. She was the daughter of Gov. Simon Bradstreet and Anne Dudley.

Hubert Hathaway

b. 1878

Sarah Bradstreet

b. circa 1656

Sarah Bradstreet was born circa 1656 at Topsfield, Essex Co., MA. She was the daughter of Gov. Simon Bradstreet and Anne Dudley.

William Lee1

b. 1739, d. 1795

William Lee was born in 1739.1 He was the son of Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell.1 William Lee died in 1795.1

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia.

Rheuben Hathaway

b. 1882

Bobby Murray Hathaway

d. 8 March 1939

Bobby Murray Hathaway was the son of Murray Lindley Hathaway and Emma Liza English. Bobby Murray Hathaway died on 8 March 1939 at Winfield, Henry Co., IA. He was buried at Saint Charles Cemetery, South township, Madison Co., IA.

Nancy (?)1

b. circa 1816

Nancy (?) was born circa 1816.1 She married Roland Holcombe, son of Luman Holcombe and Chloe Alderman, circa 1847.1

Citations

- [S67] 1850 Federal Census,, On-line Database.

Richard Lee1

b. 1618, d. 1664

Richard Lee was born in 1618.1 He was baptized on 22 March 1618.2 He was the son of John Lee and Jane Hancock.2 Richard Lee married Anne Constable in 1642 or 1642.1 Richard Lee died in 1664.1

Children of Richard Lee and Anne Constable

- John Lee3 b. 1643, d. 1673

- Richard Henry Lee Jr.+1 b. 1647, d. 1715

- Francis Lee4 b. 1648, d. Nov 1714

- William Lee4 b. 1651, d. 1696

- Hancock Lee+5 b. 1653, d. 1729

- Elizabeth Lee1 b. 1654

- Anne Lee1 b. 1654, d. 1701

- Charles Lee6 b. 1656, d. 1700

Charles Lee1

b. 1656, d. 1700

Charles Lee was born in 1656.1 He was the son of Richard Lee and Anne Constable.1 Charles Lee died in 1700.1

Citations

- [S688] Paul C. Nagel, Lees of Virginia, page 14.

Thomas Randolph1

b. June 1683, d. 1729

Thomas Randolph was born in June 1683.1 He was the son of William Randolph and Mary Isham. Thomas Randolph married Judith Fleming on 16 October 1712.1 Thomas Randolph died in 1729.1

Children of Thomas Randolph and Judith Fleming

- Col. William Randolph+1 b. 1713, d. 1745

- Mary Isham Randolph+1

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Mary Forth1

d. 1615

Mary Forth married John Winthrop on 16 April 1605 at Great Stambridge, Essex, England.1,2 Mary Forth died in 1615.1

Child of Mary Forth and John Winthrop

- Gov. John Winthrop Jr.+1 b. 12 Feb 1606, d. 5 Apr 1676

Citations

- [S690] ANB, online http://www.anb.org

- [S820] Scott C. Steward and Chip Rowe, Robert Winthrop, page 37.

Col. William Randolph II1

b. 6 November 1681, d. 19 October 1742

Col. William Randolph II was born on 6 November 1681 at Turkey Island, Henrico Co., VA.1 He was the son of William Randolph and Mary Isham. Col. William Randolph II married Elizabeth Beverley on 22 June 1709.1 Col. William Randolph II died on 19 October 1742 at age 60.1 He was buried at Turkey Island, Henrico Co., VA.

Children of Col. William Randolph II and Elizabeth Beverley

- Beverly Randolph b. 27 Dec 1710, d. 1 Jan 1713

- William Randolph III b. 14 Feb 1711, d. 15 Sep 1722

- Beverley Randolph b. 12 Nov 1713

- Elizabeth Randolph1 b. 24 Oct 1715

- Peter Randolph+1 b. 20 Oct 1717, d. 8 Jul 1767

- Mary Randolph+ b. 21 Jul 1719

- William Randolph1 b. 22 Nov 1720

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Thomasine Clopton1

d. 1616

Thomasine Clopton married John Winthrop on 6 December 1615 at Groton, England.1,2 Thomasine Clopton died in 1616.1

Citations

- [S690] ANB, online http://www.anb.org

- [S820] Scott C. Steward and Chip Rowe, Robert Winthrop, page 37.

William Stith1

b. 1707, d. 19 September 1755

William Stith was born in 1707.1 He was the son of Capt John Stith and Mary Randolph.1 William Stith died on 19 September 1755.1

Citations

- [S689] Jonathan Daniels, Randolphs of Virginia.

Margaret Tyndal1

d. 1647

Margaret Tyndal married John Winthrop in April 1618 at Great Maplestead, England.1,2 Margaret Tyndal died in 1647 at Boston, Suffolk Co., MA.1

Margaret, the third wife of Governor John Winthrop (1588-1649) of Massachusetts, was born at Much (Great) Maplestead in Essex County, England, the daughter of Sir John Tyndal, a master in the Court of Chancery, and Lady Anne Egerton. Her early life is unrecorded, but she appears to have received the education deemed appropriate for a young Puritan gentlewoman of the period. Judging from the correspondence of her adult years, she was highly literate, well versed in theology, and skilled in the management of a complex household. Margaret Tyndal was twenty-five when her father was shot and killed by a disgruntled client on 12 November 1616, as he entered his chamber in Lincoln's Inn. Margaret's reaction to her father's violent death is unknown, but a letter from her brother Arthur to their mother Lady Anne Tyndal, days after the assassination, hints that the controversy raised by the murdering client had threatened family honor. Arthur Tyndal praised God "who hath wrought wounderously alreadie in stoppeing the mouthes of malicious and naughtie people," adding that, "All the graue examiners of that business proclaime my fathers integritie and say if it had been theire case they must haue been subiect to the pistol to, for they would haue donne as he did."

Within a year of her father's death, Margaret Tyndal was being courted by the twice-widowed John Winthrop, a lawyer, Puritan, and heir to "Groton Manor" in Suffolk County. Her family was initially apprehensive about the intended marriage, since the thirty-year-old Winthrop had not received title to his father's estate and his income was therefore limited. The Tyndals' objections evidently carried weight: Adam Winthrop gave over the lordship of Groton Manor to his son sometime before John's marriage to Margaret in 1618. Her dowry, which consisted of Tyndal lands, was substantial. As the young mistress of Groton Manor she was incorporated into the household of her parents-in-law Adam and Anne Winthrop, whom she addressed as father and mother. She also became a surrogate mother to her husband's four surviving children by his first wife, who ranged in age from three to twelve. Social life at Groton was typical of gentry hospitality. Both the Winthrops and the Tyndals had extensive kinship ties, and visits between friends and relatives were common.

On 24 March 1619, after forty hours of "sore travayle," Margaret Winthrop gave birth to the first of her five children, after which she nearly died of a fever. For the first twelve years of their marriage, John Winthrop was often absent from home for weeks at a time, while he served as a legal counsel in Parliament and then as a Common Attorney in the Court of Wards and Liveries. Like other women alone, Margaret Winthrop acted as a "deputy husband" in overseeing the estate and household. During these periods, she exchanged letters with her husband in which she often belittled her capabilities, as female decorum dictated, while in practice proving herself more than competent in fulfilling her domestic responsibilities. She shared with her husband the urgent mission of completing the minutiae of daily tasks as a religious duty. Writing to him in November 1627, she teasingly commented: "I haue many resons to make me loue thee whearof I will name to. first because thou louest god, and secondly because that thou louest me. If these to ware wantinge all the rest would be eclipsed, but I am a bad huswife to be so longe from them, but I must needs borowe a little time to talke with thee."

There were times when she exerted her authority. When John Winthrop considered moving the family to a London suburb where he could commute to the city via the Thames River, Margaret Winthrop and her mother scotched the plan, arguing that the river route was too dangerous. Yet the dangers of a trans-Atlantic voyage failed to dampen her enthusiasm for the planned Puritan migration to Massachusetts Bay. In October 1629 the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Company elected John Winthrop governor. When he embarked for New England with the first wave of settlers in April 1630, Margaret Winthrop remained behind at Groton with her stepson John Winthrop, Jr. (1606-1676), and her two youngest children. Her correspondence of 1630-1631 focused on the detailed preparations for her own departure. When Boston minister John Wilson returned to England in 1631 for his wife Elizabeth, who was "more auerce then ever" to cross the Atlantic, Margaret Winthrop expressed a thinly veiled disapproval to John Winthrop, Jr., in May 1631: "I maruiell what mettall she is made on. shure she will yeald at last, or elce we shal want him [Wilson] excedingly in new england." Some days later she wrote that if Wilson stayed in England with his wife, "it will disharten many that would be wiling to goe." As for herself, she resolved "to goe for New England as spedyly as I can with any Convenience." Needing money, she set about collecting rents from the tenants at Groton, who complained "of the hardnesse of the times."

Margaret Winthrop's determination to have all of her children in New England overrode her husband's suggestion that the eighteen-month-old Anne might stay behind with his sister. "For our little daughter, doe as thou thinkest best," he wrote; "the Lord direct thee in it. if thou bringest her, she wilbe more trouble to thee in the shipp then all the rest." Margaret Winthrop traveled with her children in the company of John Winthrop, Jr., and his wife aboard the Lyon, which arrived at Boston on 2 November 1631. One week into the voyage, the baby Anne had died.

Life on the Massachusetts frontier brought new and familiar challenges. In November 1637, during the brutal Pequot War and the divisive Antinomian controversy, Margaret Winthrop once again corresponded with her husband across the relatively short distance between Boston and Newtowne (Cambridge) where he was presiding over the General Court's examination of their neighbor Anne Hutchinson. Writing from "Sad Boston" on 15 November, she sounded close to despair: " . . . sad thougts posses my sperits, and I cannot repulce them which makes me unfit for any thinge wondringe what the lord meanes by all these troubles amounge us. shure I am that all shall work to the best." Two days later, John Winthrop responded in kind: "I suppose thou hearest much newes from hence:

it may be some greiueous to thee: but be not troubled. I assure thee thinges goe well, and they must needs doe so, for God is with us, and thou shalt see a happy issue." In fact, by 1642, life in Massachusetts seemed singularly blessed compared to the turmoil of civil war in England, "When I thinke of the trublesome times and manifolde destractions that are in our natiue contrye," Margaret Winthrop wrote, "I thinke we doe not pryse our happynesse heare as we haue ca[u]se."

In May 1647 a respiratory disease spread throughout New England, from which she died in Boston. As in life, Margaret Winthrop's historical identity has been defined by her role as the wife of Governor John Winthrop. Their correspondence has illuminated the Puritan ideal of companionate marriage. She was praised by her nineteenth-century biographer as "the emblem and personification of . . . the Puritan wife and mother" (Earle, p. 334); and by a twentieth-century historian as "one of the most appealing [women] in American history" (Morgan, p. 13). Unfortunately, this mystique has tended to obscure her leadership role and she deserves to be recognized among her contemporaries as a woman of social and religious authority. 1

Margaret, the third wife of Governor John Winthrop (1588-1649) of Massachusetts, was born at Much (Great) Maplestead in Essex County, England, the daughter of Sir John Tyndal, a master in the Court of Chancery, and Lady Anne Egerton. Her early life is unrecorded, but she appears to have received the education deemed appropriate for a young Puritan gentlewoman of the period. Judging from the correspondence of her adult years, she was highly literate, well versed in theology, and skilled in the management of a complex household. Margaret Tyndal was twenty-five when her father was shot and killed by a disgruntled client on 12 November 1616, as he entered his chamber in Lincoln's Inn. Margaret's reaction to her father's violent death is unknown, but a letter from her brother Arthur to their mother Lady Anne Tyndal, days after the assassination, hints that the controversy raised by the murdering client had threatened family honor. Arthur Tyndal praised God "who hath wrought wounderously alreadie in stoppeing the mouthes of malicious and naughtie people," adding that, "All the graue examiners of that business proclaime my fathers integritie and say if it had been theire case they must haue been subiect to the pistol to, for they would haue donne as he did."

Within a year of her father's death, Margaret Tyndal was being courted by the twice-widowed John Winthrop, a lawyer, Puritan, and heir to "Groton Manor" in Suffolk County. Her family was initially apprehensive about the intended marriage, since the thirty-year-old Winthrop had not received title to his father's estate and his income was therefore limited. The Tyndals' objections evidently carried weight: Adam Winthrop gave over the lordship of Groton Manor to his son sometime before John's marriage to Margaret in 1618. Her dowry, which consisted of Tyndal lands, was substantial. As the young mistress of Groton Manor she was incorporated into the household of her parents-in-law Adam and Anne Winthrop, whom she addressed as father and mother. She also became a surrogate mother to her husband's four surviving children by his first wife, who ranged in age from three to twelve. Social life at Groton was typical of gentry hospitality. Both the Winthrops and the Tyndals had extensive kinship ties, and visits between friends and relatives were common.

On 24 March 1619, after forty hours of "sore travayle," Margaret Winthrop gave birth to the first of her five children, after which she nearly died of a fever. For the first twelve years of their marriage, John Winthrop was often absent from home for weeks at a time, while he served as a legal counsel in Parliament and then as a Common Attorney in the Court of Wards and Liveries. Like other women alone, Margaret Winthrop acted as a "deputy husband" in overseeing the estate and household. During these periods, she exchanged letters with her husband in which she often belittled her capabilities, as female decorum dictated, while in practice proving herself more than competent in fulfilling her domestic responsibilities. She shared with her husband the urgent mission of completing the minutiae of daily tasks as a religious duty. Writing to him in November 1627, she teasingly commented: "I haue many resons to make me loue thee whearof I will name to. first because thou louest god, and secondly because that thou louest me. If these to ware wantinge all the rest would be eclipsed, but I am a bad huswife to be so longe from them, but I must needs borowe a little time to talke with thee."

There were times when she exerted her authority. When John Winthrop considered moving the family to a London suburb where he could commute to the city via the Thames River, Margaret Winthrop and her mother scotched the plan, arguing that the river route was too dangerous. Yet the dangers of a trans-Atlantic voyage failed to dampen her enthusiasm for the planned Puritan migration to Massachusetts Bay. In October 1629 the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Company elected John Winthrop governor. When he embarked for New England with the first wave of settlers in April 1630, Margaret Winthrop remained behind at Groton with her stepson John Winthrop, Jr. (1606-1676), and her two youngest children. Her correspondence of 1630-1631 focused on the detailed preparations for her own departure. When Boston minister John Wilson returned to England in 1631 for his wife Elizabeth, who was "more auerce then ever" to cross the Atlantic, Margaret Winthrop expressed a thinly veiled disapproval to John Winthrop, Jr., in May 1631: "I maruiell what mettall she is made on. shure she will yeald at last, or elce we shal want him [Wilson] excedingly in new england." Some days later she wrote that if Wilson stayed in England with his wife, "it will disharten many that would be wiling to goe." As for herself, she resolved "to goe for New England as spedyly as I can with any Convenience." Needing money, she set about collecting rents from the tenants at Groton, who complained "of the hardnesse of the times."

Margaret Winthrop's determination to have all of her children in New England overrode her husband's suggestion that the eighteen-month-old Anne might stay behind with his sister. "For our little daughter, doe as thou thinkest best," he wrote; "the Lord direct thee in it. if thou bringest her, she wilbe more trouble to thee in the shipp then all the rest." Margaret Winthrop traveled with her children in the company of John Winthrop, Jr., and his wife aboard the Lyon, which arrived at Boston on 2 November 1631. One week into the voyage, the baby Anne had died.

Life on the Massachusetts frontier brought new and familiar challenges. In November 1637, during the brutal Pequot War and the divisive Antinomian controversy, Margaret Winthrop once again corresponded with her husband across the relatively short distance between Boston and Newtowne (Cambridge) where he was presiding over the General Court's examination of their neighbor Anne Hutchinson. Writing from "Sad Boston" on 15 November, she sounded close to despair: " . . . sad thougts posses my sperits, and I cannot repulce them which makes me unfit for any thinge wondringe what the lord meanes by all these troubles amounge us. shure I am that all shall work to the best." Two days later, John Winthrop responded in kind: "I suppose thou hearest much newes from hence:

it may be some greiueous to thee: but be not troubled. I assure thee thinges goe well, and they must needs doe so, for God is with us, and thou shalt see a happy issue." In fact, by 1642, life in Massachusetts seemed singularly blessed compared to the turmoil of civil war in England, "When I thinke of the trublesome times and manifolde destractions that are in our natiue contrye," Margaret Winthrop wrote, "I thinke we doe not pryse our happynesse heare as we haue ca[u]se."

In May 1647 a respiratory disease spread throughout New England, from which she died in Boston. As in life, Margaret Winthrop's historical identity has been defined by her role as the wife of Governor John Winthrop. Their correspondence has illuminated the Puritan ideal of companionate marriage. She was praised by her nineteenth-century biographer as "the emblem and personification of . . . the Puritan wife and mother" (Earle, p. 334); and by a twentieth-century historian as "one of the most appealing [women] in American history" (Morgan, p. 13). Unfortunately, this mystique has tended to obscure her leadership role and she deserves to be recognized among her contemporaries as a woman of social and religious authority. 1

Citations

- [S690] ANB, online http://www.anb.org

- [S820] Scott C. Steward and Chip Rowe, Robert Winthrop, page 37.

William Randolph III

b. 14 February 1711, d. 15 September 1722

William Randolph III was born on 14 February 1711 at Turkey Island, Henrico Co., VA. He was the son of Col. William Randolph II and Elizabeth Beverley. William Randolph III died on 15 September 1722 at age 11; at sea on his way to England.

Martha Rainsborough1,2

Citations

- [S690] ANB, online http://www.anb.org

- [S820] Scott C. Steward and Chip Rowe, Robert Winthrop, page 37.

Chiswell Dabney Langhorne

b. 4 November 1843, d. 14 February 1919

Chiswell Dabney Langhorne was born on 4 November 1843 at Lynchburg, VA. He was the son of John S. Langhorne and Sarah Elizabeth Dabney. Chiswell Dabney Langhorne died on 14 February 1919 at Richmond, VA, at age 75.

Child of Chiswell Dabney Langhorne and Nancy Witcher Keene

- Nancy Witcher Langhorne b. 19 May 1879, d. 2 May 1964

Eliza Ann Goodrich

b. 6 May 1803, d. 2 December 1867

Eliza Ann Goodrich was born on 6 May 1803 at Granby, Hartford Co., CT.1,2 She was the daughter of Hezekiah Goodrich and Millicent Holcombe. Eliza Ann Goodrich married Francis Tracy Allen on 3 November 1826 at Granby, Hartford Co., CT.1,3 Eliza Ann Goodrich died on 2 December 1867 at Granby, Hartford Co., CT, at age 64.1